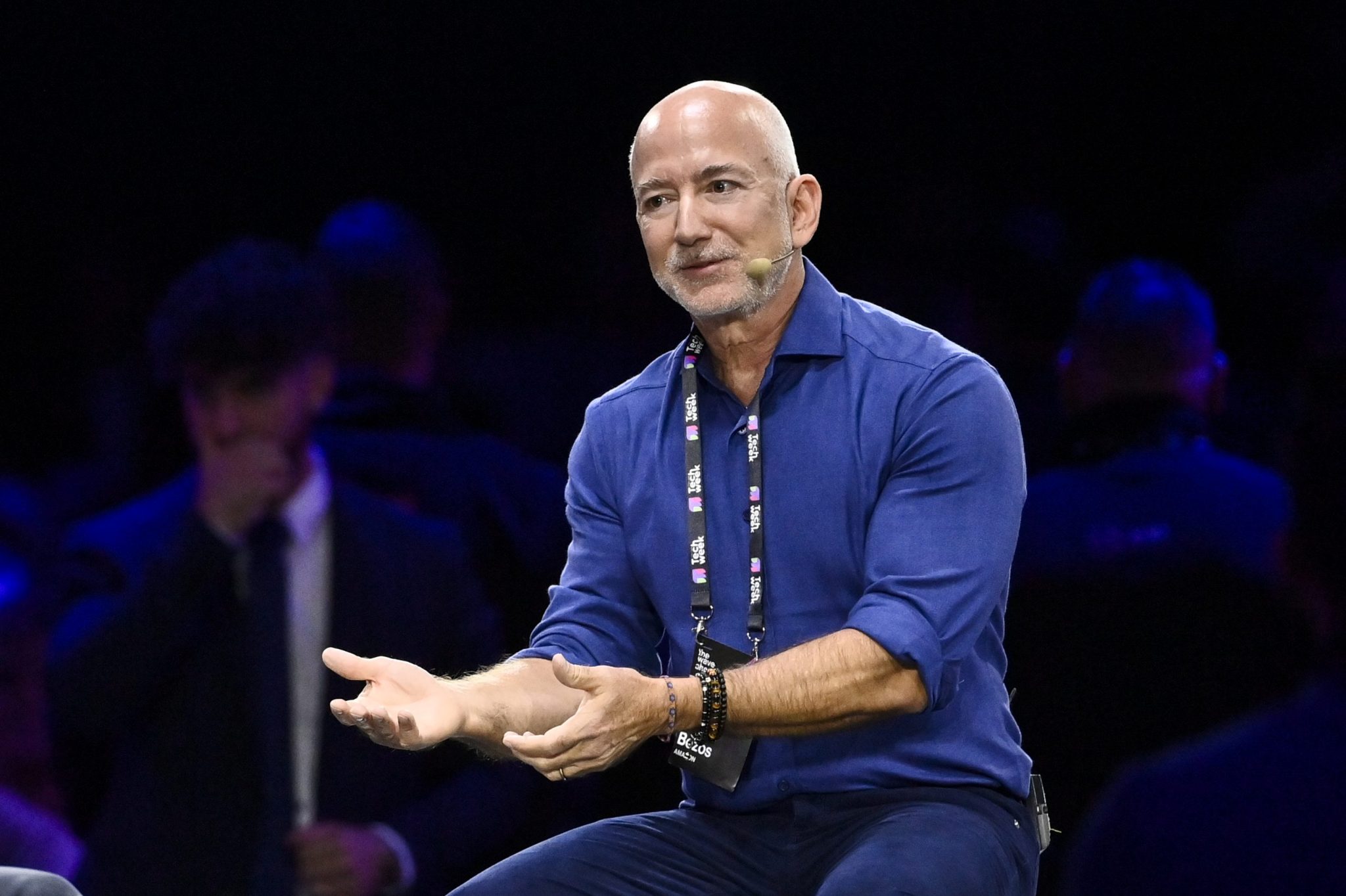

Before the McLaren CEO got a $50 million payday from his team’s F1 championship, he was a high-school dropout who got his start on Wheel of Fortune

McLaren Racing Formula 1 drivers Lando Norris and Oscar Piastri crossed the finish line at the Singapore Grand Prix on Sunday in third and fourth place respectively, cementing the team’s second consecutive Constructors’ Championship in the sport. One of the oldest teams in F1’s 76-year history, McLaren has reportedly reached an estimated worth of a record $5 billion under the leadership of CEO Zak Brown, topping Ferrari’s estimated $4.8 billion valuation in 2024. Since joining McLaren in 2016, Brown has not only capitalized on F1’s meteoric growth in the U.S. to grow the team’s sponsorship spending, but has also helped McLaren take its first constructors’ title since 1998. Given the team’s success, Brown’s payday for 2025 will no doubt rival that of his 2024 compensation worth more than $50 million (£37.3 million). But before the McLaren boss was making eight figures in the rubber-burning world of F1, he made his first fortune spinning different wheels. Born in Los Angeles, Brown was a...

McLaren Racing Formula 1 drivers Lando Norris and Oscar Piastri crossed the finish line at the Singapore Grand Prix on Sunday in third and fourth place respectively, cementing the team’s second consecutive Constructors’ Championship in the sport. One of the oldest teams in F1’s 76-year history, McLaren has reportedly reached an estimated worth of a record $5 billion under the leadership of CEO Zak Brown, topping Ferrari’s estimated $4.8 billion valuation in 2024. Since joining McLaren in 2016, Brown has not only capitalized on F1’s meteoric growth in the U.S. to grow the team’s sponsorship spending, but has also helped McLaren take its first constructors’ title since 1998. Given the team’s success, Brown’s payday for 2025 will no doubt rival that of his 2024 compensation worth more than $50 million (£37.3 million). But before the McLaren boss was making eight figures in the rubber-burning world of F1, he made his first fortune spinning different wheels. Born in Los Angeles, Brown was a high-school dropout with aspirations only for a career in baseball, which fizzled alongside his formal education. “I was not a good student. I didn’t go, and then when I did go, I got in trouble—a lot of fighting,” Brown said in an episode of The Bottom Line podcast released in July. “I actually broke my high school president’s jaw in a fight. That’s what got me thrown out at the end.” But during one of Brown’s (self-admitted) few days he was at school in 1984, showrunners for American quiz show juggernaut Wheel of Fortune went in search of students for its Teen Week tapings. Brown became one of 15 kids to compete on the show, and he won the first two rounds, taking with him a pair of watches as his winnings. With an interest in F1 piqued after his family attended a race in 1981 and a family connection in motorsports, Brown used his newfound earnings to begin his racing career. “I went and turned around and sold those watches in a pawn shop, bought a go-kart. And that’s how my racing career began,” Brown said. “It wasn’t part of any sort of master plan. It’s just how it all unfolded. So probably safe to say I’m the only person in racing that has a resume that starts the Wheel of Fortune.” Recovery from being financially ‘on the brink’ Brown’s career in the driver’s seat did not materialize with a drive in F1. He competed in British Formula Three, the Formula Opel-Lotus Benelux Series, and North America’s Toyota Atlantic Series the year he won Wheel of Fortune. But he eventually pivoted to the business side of the sport, founding his own marketing company Just Marketing Inc., using the connections he made in racing to chase sponsorships for himself and others. By the time Brown sold a majority of the company in 2008 to Spire Capital and Credit Suisse (Chime Communications bought the former in 2013), JMI was one of the biggest global motorsport marketing agencies. When Brown joined McLaren about a decade ago, the company was in need of Brown’s business sensibilities. The team initially attributed some of its on-track struggles to a power unit problem, but when it switched engine manufacturers, problems persisted. “There was an arrogance, a denial that once we swapped the power unit we were going to be back to McLaren,” Brown told Fortune in March. “And when that didn’t happen, it was pretty sobering.” On top of juggling internal politics of company leadership, Brown was also contending with financial woes. At the end of 2020, following a pandemic-stricken F1 season, McLaren sold part of its team to MSP Sports Capital, an American sports investment group. “We were definitely on the brink,” Brown told The Athletic. “We were paying all our bills…But we were in a situation where if we didn’t have a cash injection, we would have been a risk at (not) starting the year. “I needed to protect the team from them being aware so everyone could remain in the very positive, energetic spirits they were bringing because the team was progressing nicely,” he continued. “It wasn’t a comfortable place at all.” A $235.8 million (£185 million) investment and the embrace of what Brown calls a “no-blame culture” eventually gave McLaren what it needed to rev up its turnaround. “We win and lose together, we back each other up, and we don’t blame each other,” Brown told Fortune. “Mistakes happen, and we learn from them.” This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Advertisement